The idea, at a big club, is to have a great goalkeeper you don’t need. He’s there to field back-passes, watch wayward 30-yard strikes sail into the sixteenth row, and celebrate with nobody in particular as another goal brings the lead to 3-0. If he plays for Barcelona or Manchester City, maybe he functions as an auxiliary holding midfielder from time to time. His ability to lean left and dive right, push a strong header over the bar, anticipate a chip: these are to remain theoretical for the full ninety minutes.

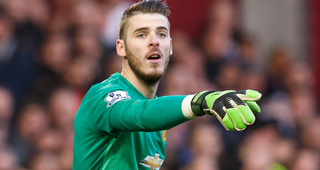

This dream—a manager and partisan’s dream, not really what a neutral is looking for—sometimes comes to pass, and when it does the big club keeper becomes a happier mirror image of the isolated small club striker. He’s incidental to the result; we don’t get to see what he can do. There are games in which José Mourinho could get away with putting a standee of David de Gea in goal, and he’s probably particularly pleased with those matches, but it’s obviously better, if you’re just somebody watching Manchester United at a bar, hoping something interesting will happen, for a keeper with de Gea’s gifts to play a big part in his team’s success. If a guy can lunge off the wrong foot and still get to a top corner strike, that’s something you want to see as often as possible.

So in a way, United’s back line—good, but shaky; organized imperfectly—did us a favor last season in (accidentally) letting the Spaniard cook, their league-best goals conceded tally having a lot more to do with the de Gea than Chris Smalling or Ashley Young. Over 37 league matches and a handful of cup and European games, he put together a highlight reel for the ages. Every decent keeper accumulates a few acrobatic beauties over the course of a year, but the very best ones cause our brains to short-circuit with such regularity that watching them becomes a paradoxical experience in expecting them to surprise you.

We know that de Gea is extraordinarily perceptive and agile, so the shifting imaginary zone that indicates where a striker needs to place the ball in order to score at any given moment is smaller than it is against, say, Lukasz Fabianski, but the mind isn’t a computer making calculations second to second, so we’re ballparking it all the time. And occasionally there is not space enough even to do that. The cross flies in early, or a defender falls down, and nothing but the pure joyful terror of A GOAL IS ABOUT TO HAPPEN trembles through us. In the midst of that sensation, the keeper flashes across our consciousness like a low-flying plane past a kitchen window and there’s a brief confusing spell where we’re certain the ball is in the back of the net but also know it isn’t. It has gone out into touch because—well, it’s possible that god is real and he’s chosen to manifest himself on Earth just to deny Sergio Aguero some happiness, but watching the replay, it appears that David de Gea has intervened. It makes sense, in retrospect, because, right, he’s the fellow who makes saves he’s not supposed to be able to make. His absurd feats become legible only through the reputation he’s built. And even then just barely.

This is the transcendent thing about being a world-class athlete: you’re a kind of disbelief merchant, performing acts that emotionally flatten people. It’s the closest a mortal can get to genuine miraculousness. Even the work of great writers and filmmakers is constrained and mediated by the grammar of their disciplines and the need for an intellect of a certain caliber to operate upon them to produce meaning. De Gea’s genius is simple, primal: he can turn his body into a kite and parry a strike he has no business getting to. We understand bodies and their motions more thoroughly than we ever do love or politics or the natural world. In fact, it’s the first thing we understand upon achieving sentience. That deep, basic, universal knowledge makes athletes better at delivering raw feeling, just by doing what they do, than any other professionals in any other field.

Which would make de Gea a saintly figure were sports not also frivolous and undignified, and were he not capable, as he demonstrated at the World Cup, of producing workmanlike cringe-comedy in addition to the transporting brilliance he normally creates. He caught hell from a Spanish press that was looking for someone to blame after the national team’s early exit from the tournament, because MARCA needed a villain and they don’t care about how good he’s been in dreary old England. De Gea’s screw-up was surely a source of personal anguish, but it was also instructive in that it reminded us of the full spectrum of possibility a keeper faces as a shot’s coming at him. An agent of the sublime can easily make a feeble doofus of himself, which is why the manager sweats whenever his team’s last line of defense has to make himself useful. Goalkeeping—both watching and doing it—is an intensely fraught, heightened experience. Were that not the case, we wouldn’t appreciate David de Gea’s talent quite as acutely as we do.

You wonder how many gobsmacking saves per season he’d make for a relegation candidate club, some leaky outfit with clumsy defenders and a wasteful midfield. He wouldn’t have much fun with it, nor would the ruddy-faced heartburn patient on the touchline, but the thought does pass through like a lazily drifting cloud, sometimes, in the middle of a sleepy-suffocating Mourinho-engineered victory: maybe the United defense should take a few steps off their opponents and allow them have a hit or two. Let David splay his skill, let him entertain us. Nobody’s beating him anyway. We’re sure of that, and yet continually, delightedly shocked by the ways he proves impenetrable.

More End-to-End Stuff: Lionel Messi, Neymar, Harry Kane, Mohamed Salah, N'Golo Kante, Thomas Partey, Paul Pogba, Cristiano Ronaldo, Mauro Icardi, Gareth Bale, Christian Pulisic